Prime numbers, like 2,57, and 47 are special 1. Unlike say 4 = 2 * 2 or 33 = 3 * 11, prime numbers can’t be written as the product of other numbers. They’re the fundamental block we express other numbers through: every natural number, 1, 2, 3, … is the product of primes 2. How many of these special prime numbers are there?

Infinitely many! A recent one-line proof by Sam Northshield shows why there are infinitely many primes 3:

0<∏psin(π/p)=∏psin(π∗(1+2∗∏p′p′)p)=0.You may wonder how sin relates to prime numbers. Why π? Why is the left less than the right?

In this post, we’ll untangle this elegant, one-line proof to reveal the answers.

Imagine

Let’s imagine there’s a fixed number of primes. What then?

Ignoring the in-between, the proof says

0<something=0.This means “something” is simultaneously equal to zero and strictly less than zero. What we imagined—that there’s a fixed number of primes—is then impossible. There must be infinitely many primes.

Now let’s untangle the “something” in between.

Step 1: 0< “Something”

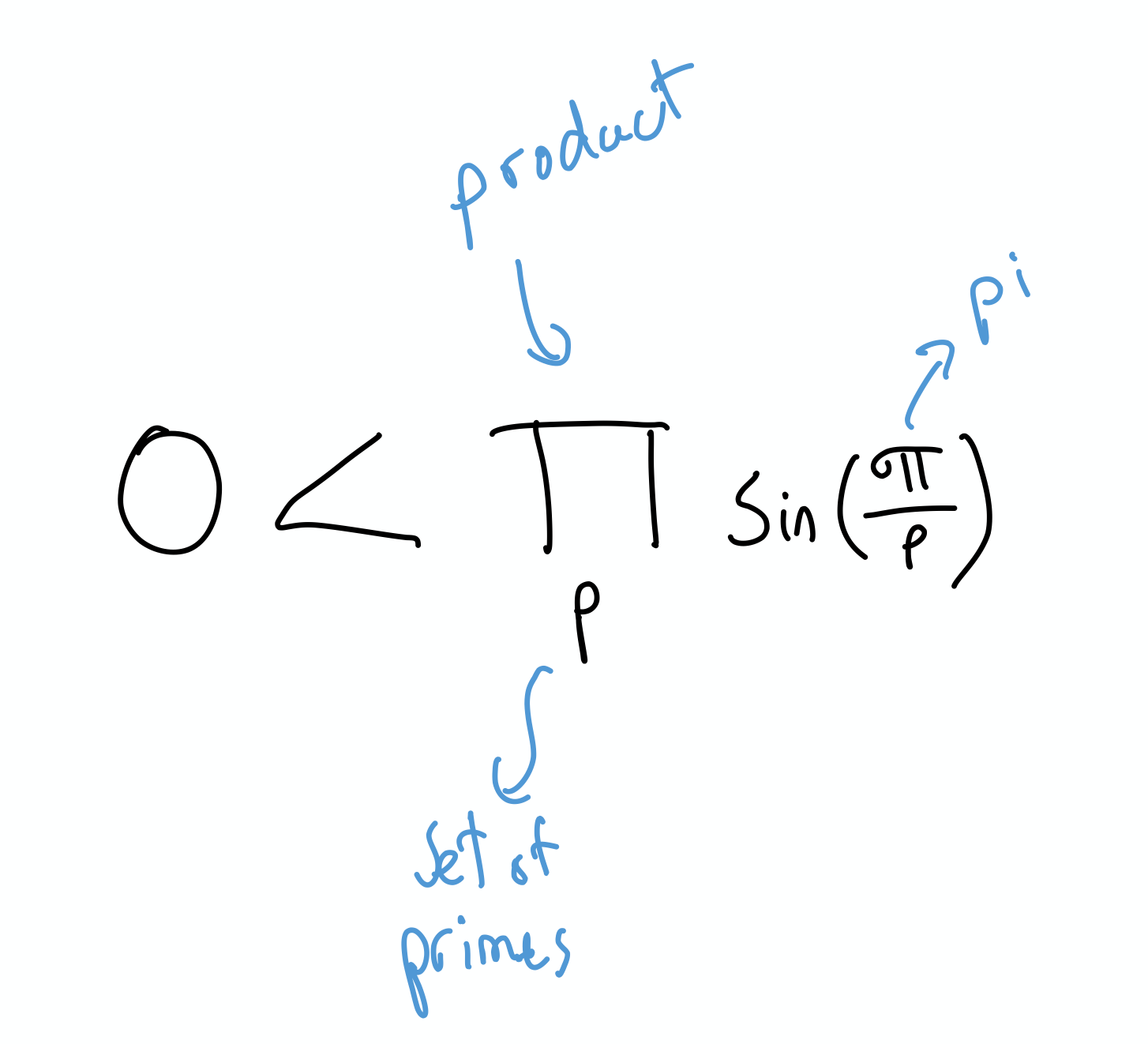

First, let’s understand what these symbols mean:

- Careful, pi = 3.14… and product look very similar.

How do we know “something” is greater than zero?

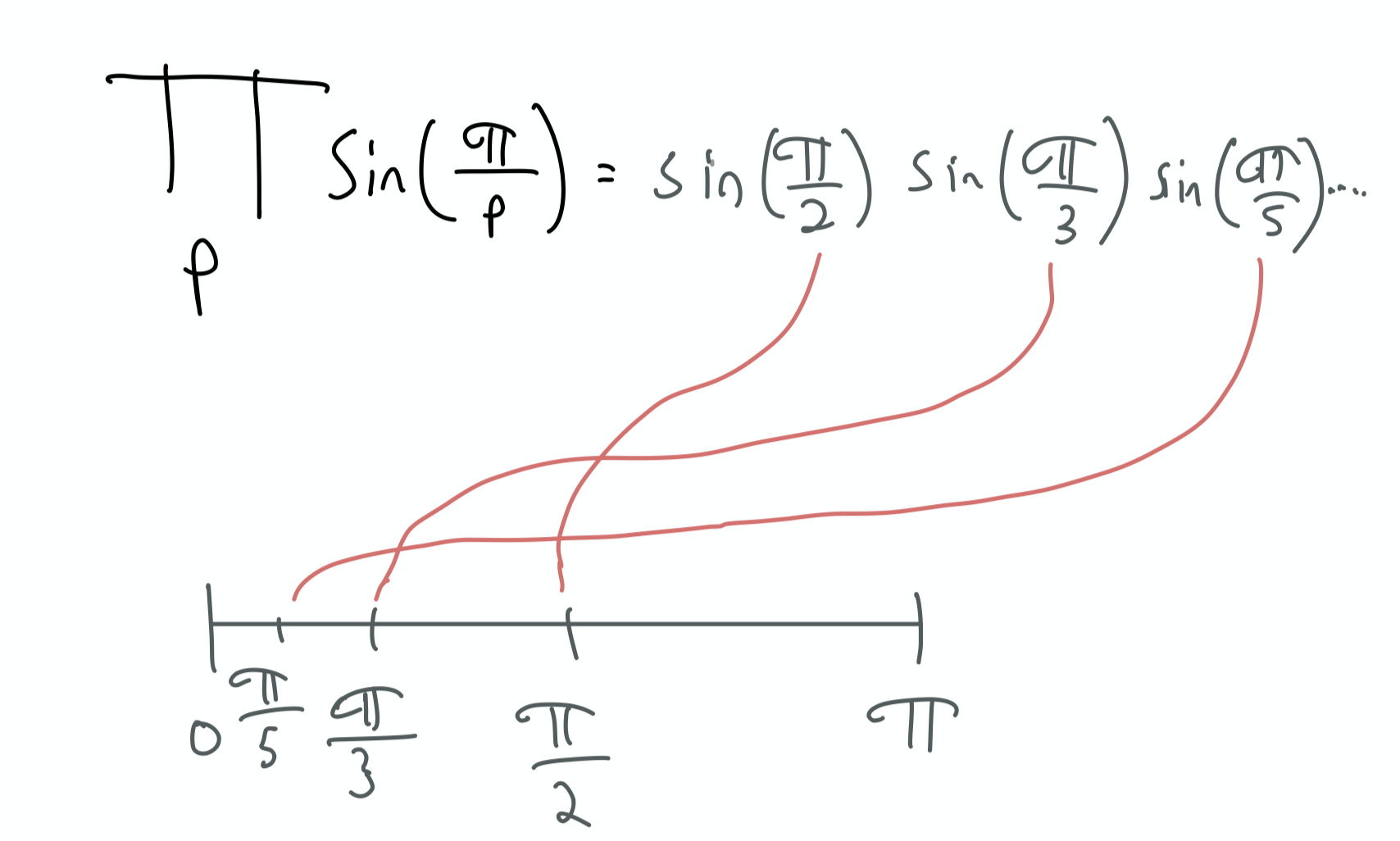

Let’s see what these values equal

Not matter which prime p we choose,

sin(π/p)>0.

This means “something” is the product of positive numbers. “Something” =∏psin(π/p)=++…+=+.

“Something” must be greater than 0.

Step 2: Rewrite “Something”

We want to rewrite “something” in a new form to see it’s also equal to zero. The proof says

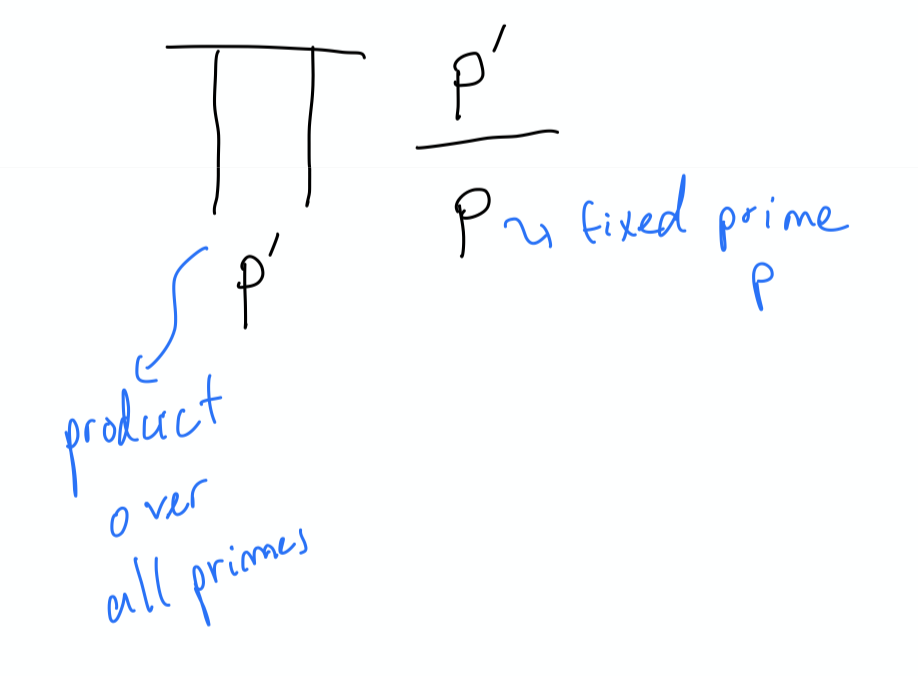

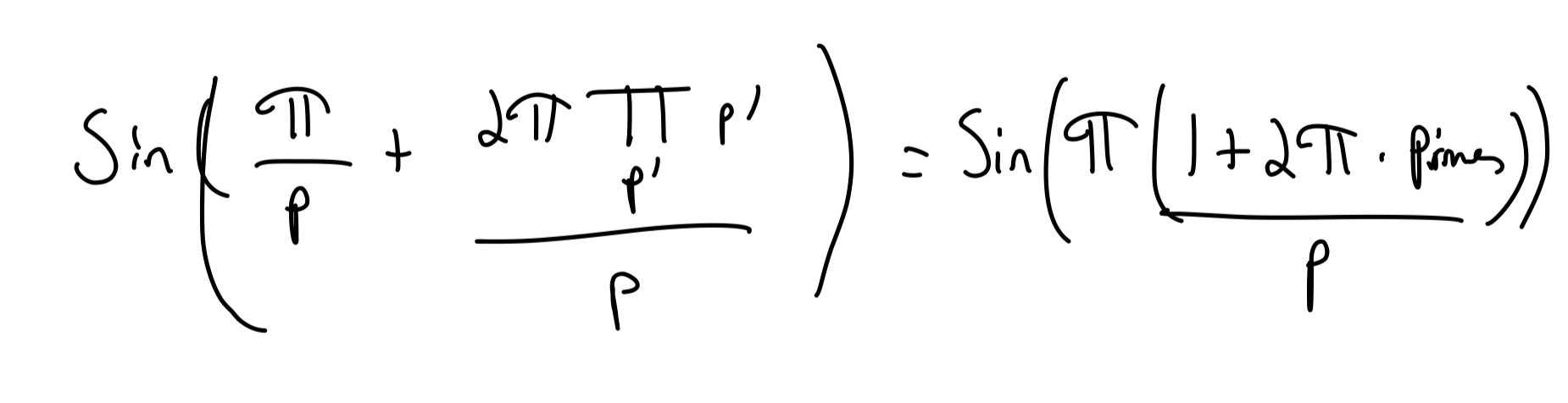

sin(π/p)=sin(π/p+2π∏p′p′/p).The product inside sin means

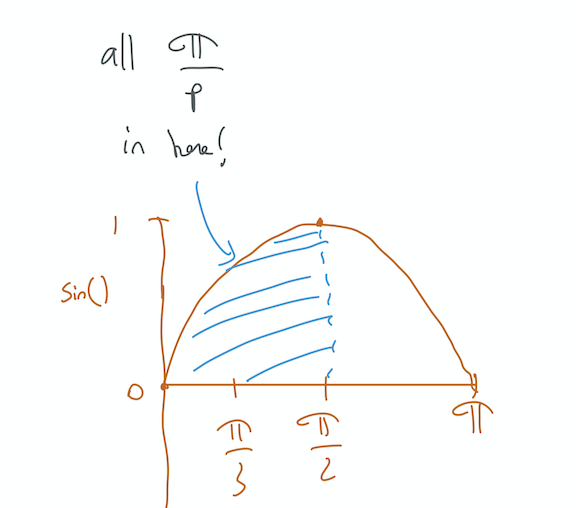

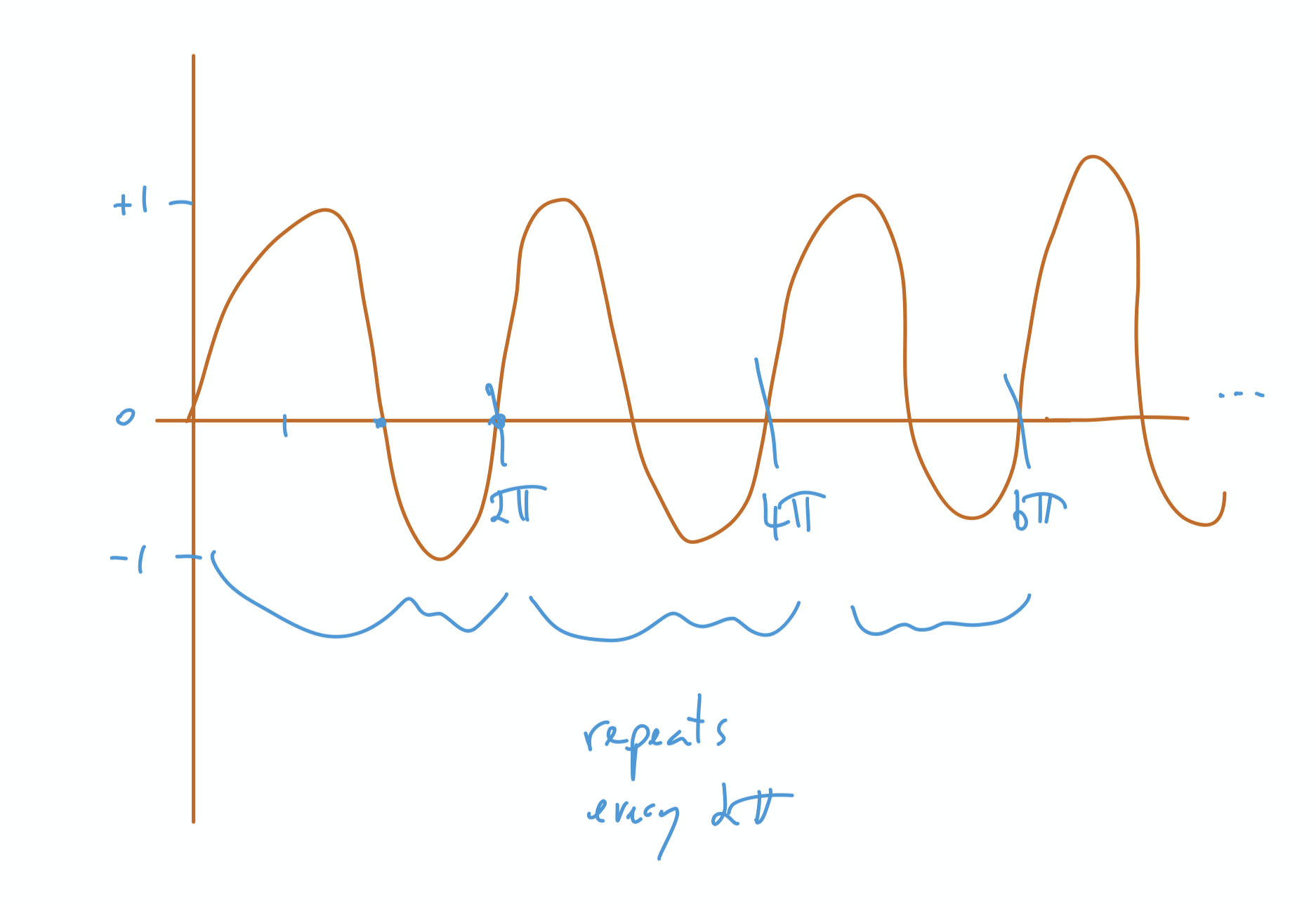

Let’s look at a graph of sin

The graph between 0 and 2π is exactly the same as that between 2π and 4π. It’s a repeating pattern every 2π. The pattern says

sin(n)=sin(n+2π#)for any # 0,1,2,….

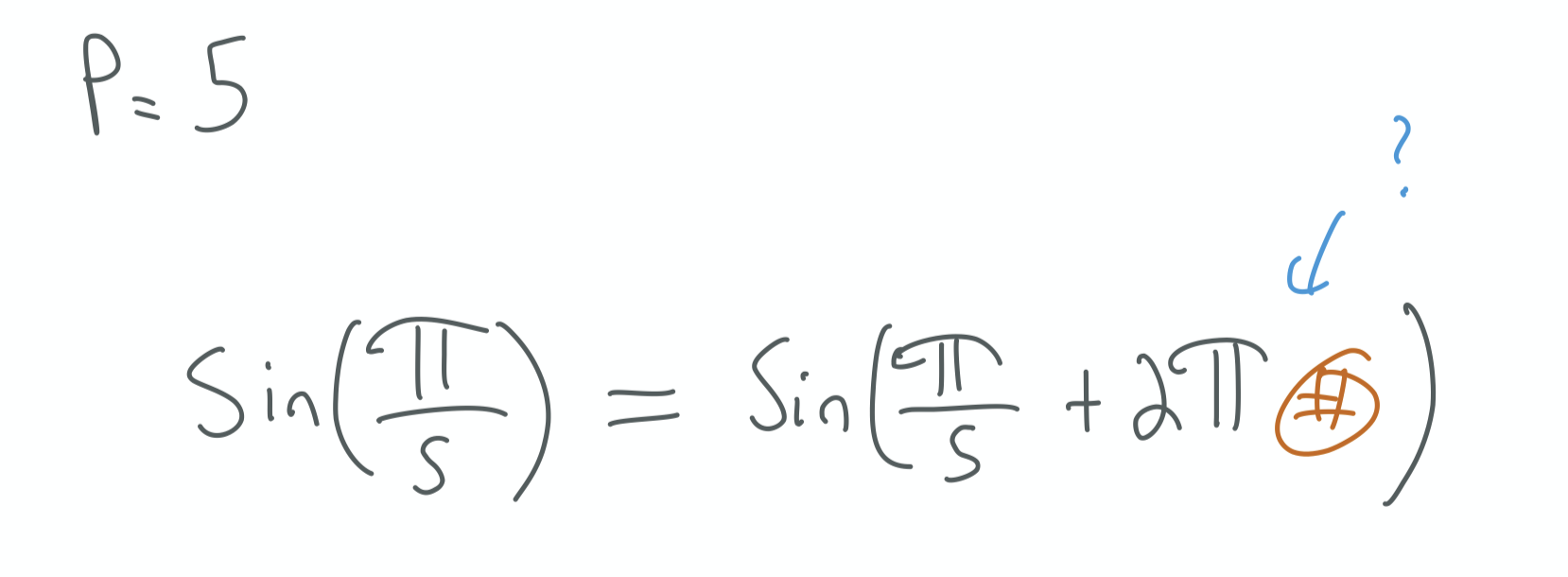

Let’s think about one case when p=5. Remember we know

no matter which orange # we choose.

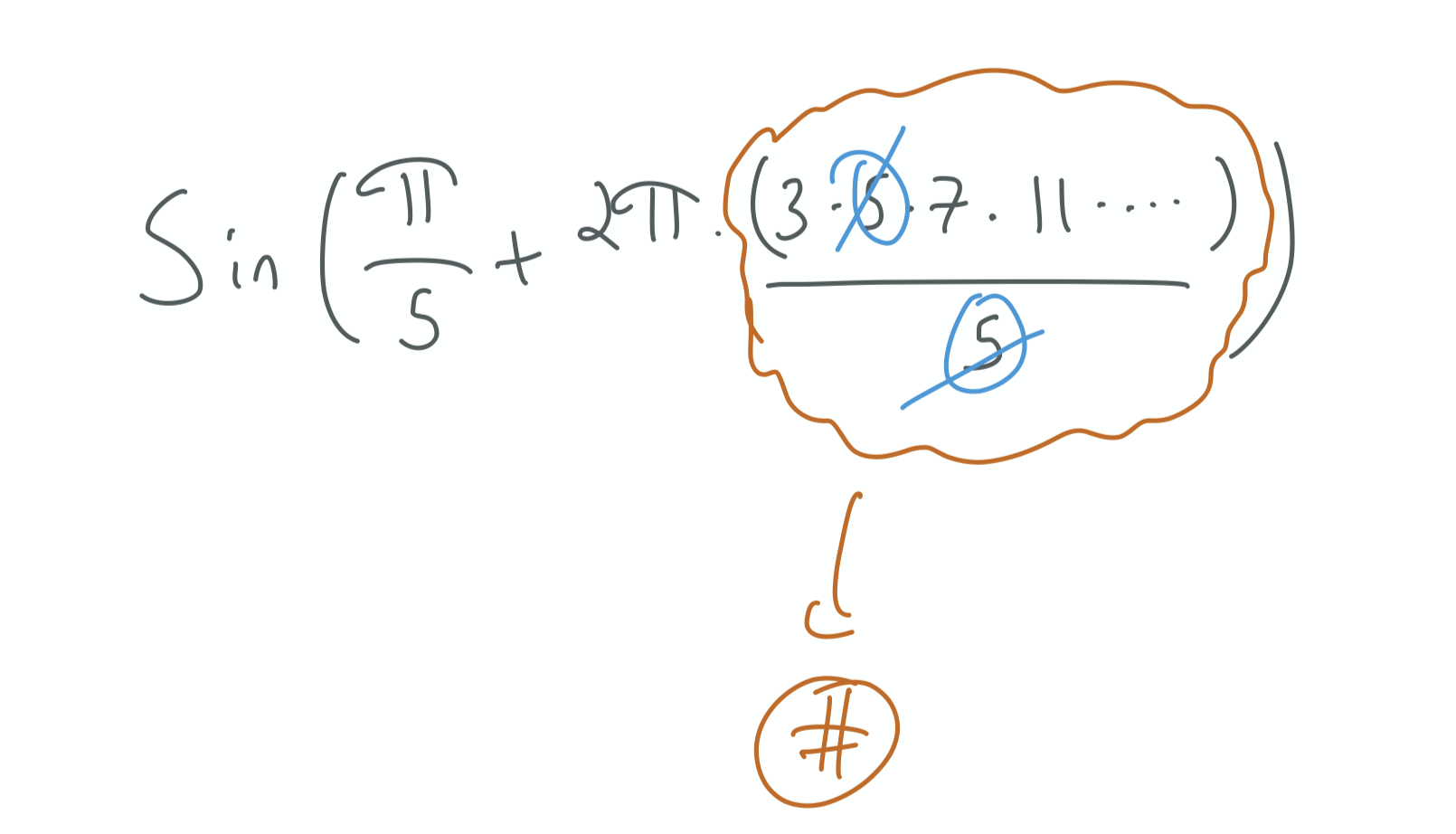

What if we choose the # to be ∏p′p′5?

Using the repeating pattern of sin we can then rewrite sin(π/5)

as

Luckily, this is true not just for p=5, but for any p. We can always find a p′ in the numerator to cancel p. For any p, we then get

sin(π/p)=sin(π/p+2π∏p′p′p).Step 3: “Something” equals 0

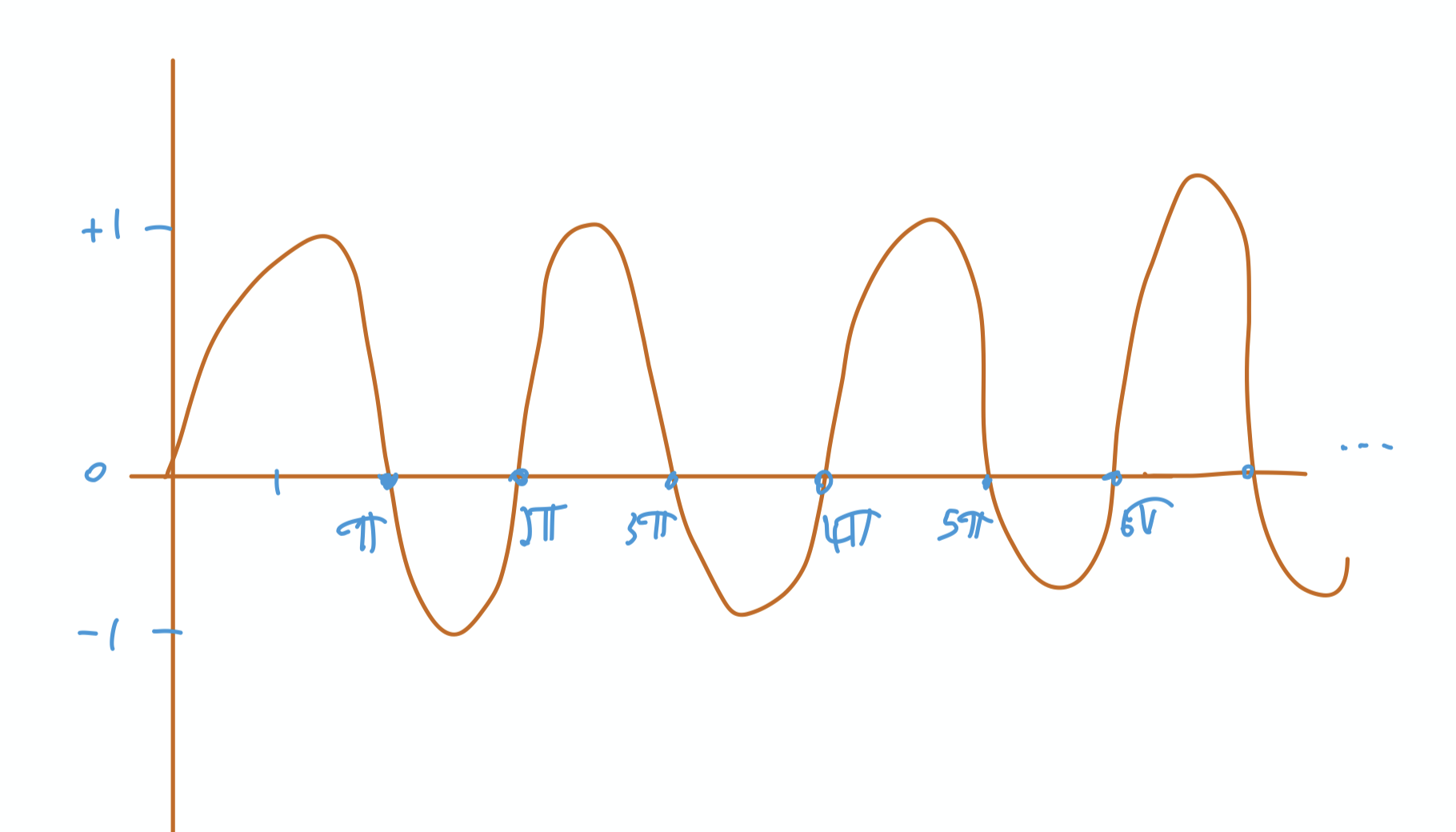

Finally, let’s see why “something” = ∏psin(π/p) is also zero. Let’s look at where sin is zero

sin(kπ)=0 for any k=0,1,2,….

Let’s rewrite the terms inside sin in a friendlier form:

by combining the terms under a common denominator.

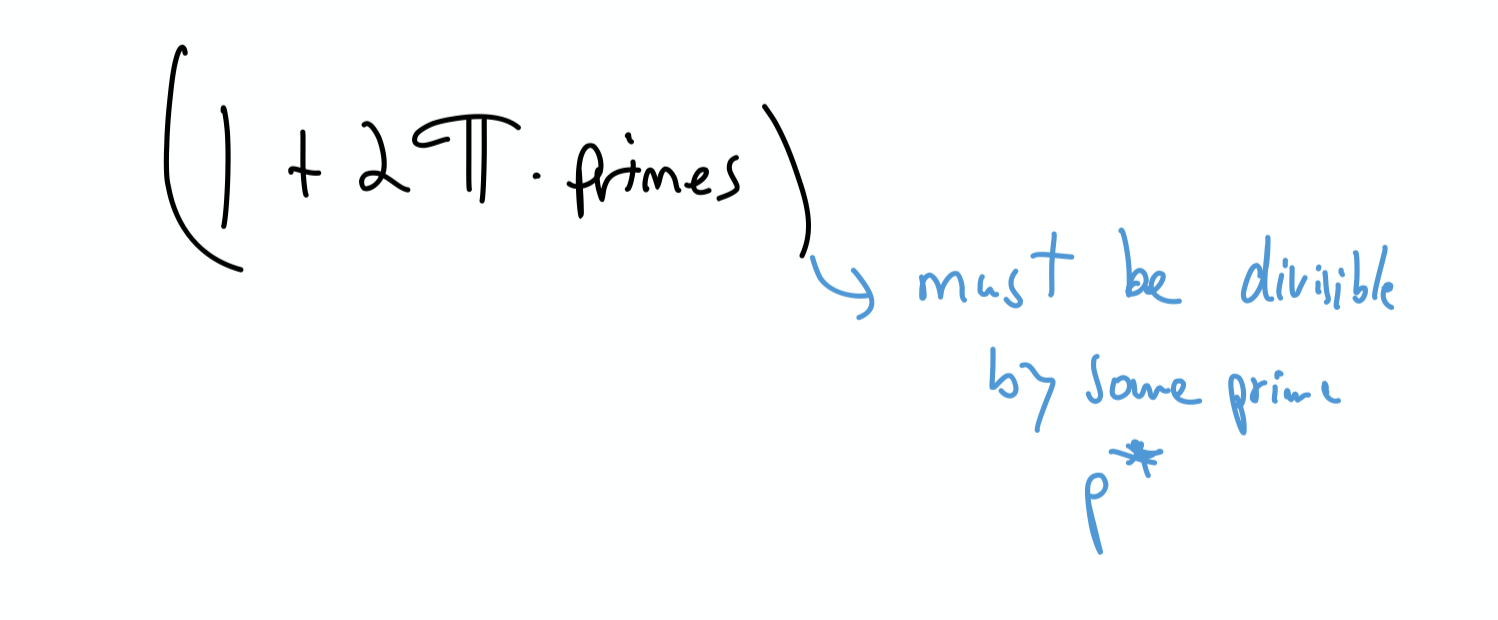

Now notice

because every natural number can be written as the product of primes.

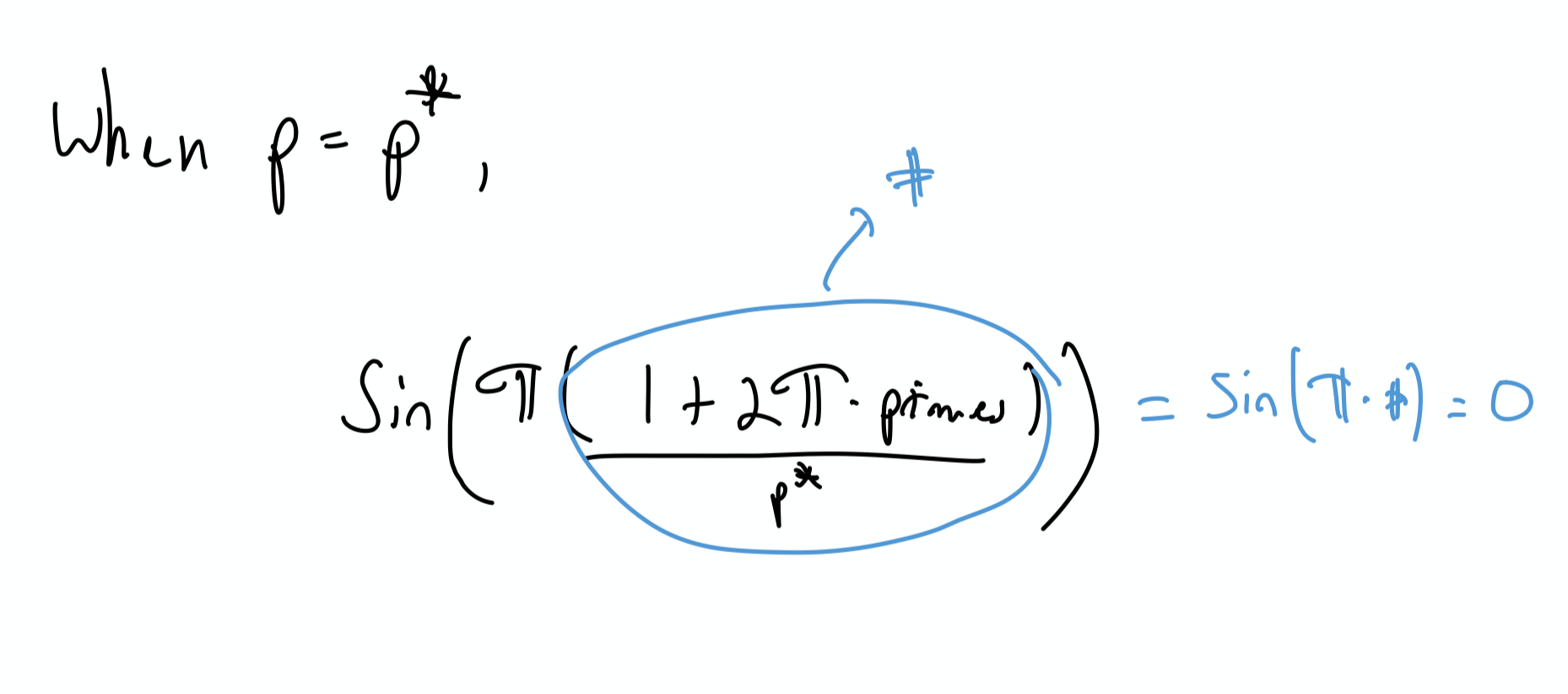

Let’s call one of those primes p∗. Then,

Now we have one term in our product that’s zero (when p=p∗), meaning

∏psin(π/p)=sin(π/2)sin(π/3)∗0∗....=0.The Punch Line

If we assume there are finitely many primes,

∏psin(π/p)=0,and from step 1

∏psin(π/p)<0.That can’t be.

We confidently conclude our original assumption is wrong. There must be infinitely many primes.

-

prime numbers are also special in an everyday sense. Finding these special numbers is what makes sending credit card info. on the internet secure ↩

-

natural numbers are 1, 2, 3, 4, …. excluding fractions or irrational numbers such as pi. ↩

-

Many other proofs exist showing there are infinitely many primes (see prime factorization). ↩